(What follows is the commencement address I gave on June 12, 2024 at the eighth grade graduation of the Northeast Woodland Chartered Public School, at Tin Mountain Conservation Center, in Albany, New Hampshire.)

I’m grateful to Mrs. Arnold for giving me the opportunity to be part of this auspicious occasion, and for having invited me to the presentation of your eighth grade projects twelve days ago, so I would have some sense of who I’m dealing with here today.

I saw that, collectively, you’re the sort of people who make maple sugar magic from tree to table, and sculpt giant mushrooms with chainsaws, and create deerhide mittens, starting with a deer. You design and stitch the hoodies that wizards wear! You make chainmail, and websites, and chainmail websites, and design video games with ZOMBIE GOATS (!), and Van der Graaf generators. As if that weren’t enough, you draft elaborate building drawings for a palatial house you could all live in together with your families, and invent and craft affordable skis out of 2x4s, reminding us along the way that we’ll always find better lumber at our local lumberyards than at the big box stores.

So I asked myself, “Self, what do I possibly have to impart to people such as these?” And the answer came to me that I must prepare you to meet the reality Logan laid out for us, a world in which ZOMBIE GOATS WILL FOLLOW US EVERYWHERE, FOREVER! (Especially, if I may say so, in high school.)

Fortunately, I’m a storyteller, which means that I live my life according to the old adage “The story is mightier than the zombie goats!”

So, I have two simple little stories for you.

I’ll begin with one my father told me for the first time when I was about your age. But he didn’t just tell it once, he told it over and over again. He would always begin the same way: “Did I ever tell you about…”as dads do. And he had, but that didn’t stop him from doing it again. But I’m grateful to him for that repetition, because that helped me remember his stories. And when I remember his stories, he’s with me still.

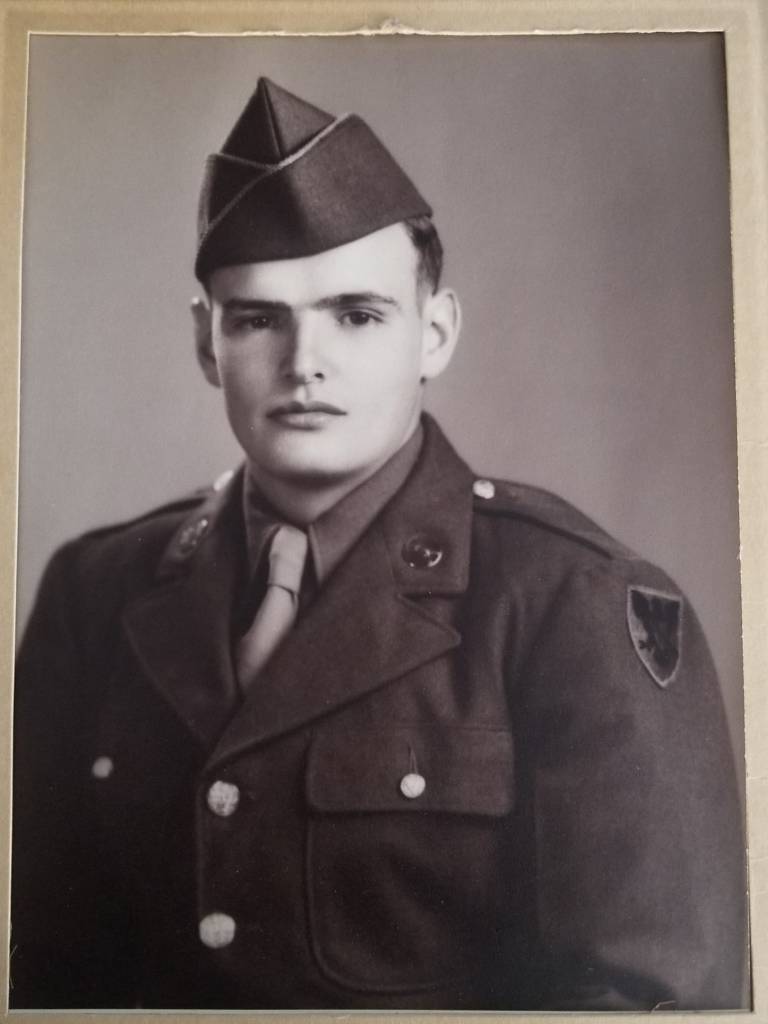

When he was still a teenager, just a few years older than you, he joined the army and went off to Europe to fight in World War II. He went through a lot over there, but this is about what happened when he was on his way home.

(Allen N. Davis, circa 1944)

In May of 1945, just a few days after the Germans surrendered, the contingent of the 86th Black Hawk Infantry Division that included my dad was transported in trucks from Mannheim, Germany to the port at Le Havre in France to ship back to the states. On the way, they camped 20 miles from Paris, and the word came down from on high that there would be two passes per squad for those who might want to go into “the City of Lights” for the evening.

If you have any inkling at all as to how the military operates, you know that those passes would have been snatched right up by the sergeants and corporals, leaving the lowly privates and privates first class like my father out of luck. Dad didn’t think this was fair, and he went to the platoon leader, Lt. Gracie, and told him so. He said, “I’ve come this far, I’m gonna see Paris.” He suggested that if he didn’t get a pass to go, he would break the rules, go AWOL, and get there by himself.

Lt. Gracie said, “Why Davis, I wouldn’t do that if I were you,” but a short while later it was announced that enough trucks would be made available that anyone at all who wanted, of any rank, could go, they just needed to get washed up and be ready in half an hour. When my father heard the good news, he poured water from his canteen into his steel battle helmet, bathed as well as he could, put on his cleanest dirty shirt, and ran for the truck.

My father told us about seeing the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, and the Notre Dame Cathedral, but what most lit him up was going to a Montmartre nightclub and seeing the dancers in a cancan show. I have to confess that that was the detail that captured my imagination, too, at first, even though I understood that the point of the story was supposed to be that my father had spoken up when he saw something he didn’t think was right.

But lately I’ve seen how it went even deeper than that, how Dad transformed a situation not just for himself but for a whole lot of other guys. You see, people didn’t travel as much back then as some do now, so for many, if not most of the men camped outside Paris that night, their time in the service would be the sum total of their European travels. But for this group of men in 1945, whatever else they survived or accomplished in their lives, they had seen Paris.

This second story is about a group of children, a little wooden-frame house, and a windstorm.

During the same period when my father was fighting in Germany, a little boy named John Robert was growing up in the American south. The only world he knew was the one he stepped out into each morning, a little corner of southern Alabama, set among thick pine forests, cotton fields and red clay roads.

Almost all their neighbors were sharecroppers, which meant they farmed the land for other people, in return for a small percentage of what the crop sold for, which kept them poor. Most of these neighbors were relatives. The adults were all uncles and aunts, and the other kids were all first and second cousins. John Robert only remembered ever seeing two white people as a small child, the mailman and a traveling salesman who came through now and then.

You know how in every neighborhood there seems to be one house where all the kids gather? Well, where John Robert lived, it was his Uncle Rabbit and Aunt Seneva’s house a half mile up the road. One day a passel of kids was playing in their red dirt yard, about fifteen in all, of all ages, mostly his siblings and cousins. Aunt Seneva was the only adult there, taking the laundry down from the clothesline. Across the cotton field, the sky started to get dark very fast, the wind picked up, and they could hear the rumble of thunder and see lightning shooting down from the distant clouds. They could see rain slanting down towards the earth.

As the first drops of rain began to come down on them and the wind continued rising, Aunt Seneva herded all the children inside. Her house was very small, just a tarpaper shack, really, and it seemed even tinier with so many kids packed into it. And it was surprisingly quiet, for being so full. All the laughter and fun and games had stopped. But it was loud outside. The rain began to drum on the tin roof, the wind rose to a howl and the house was starting to shake. The children were terrified. So was Aunt Seneva.

It didn’t stop at that—the walls of the house began to flex, as if it was breathing, and the wood plank flooring began to ripple. Then, to their horror, a corner of the house began lifting up, as if the storm was actually going to carry the house to the land of Oz, with all of them in it!

That was when Aunt Seneva took action. “Line up and hold hands,” she said, raising her voice against the din of the wind and rain. “Line up and hold hands, all of you!” The children did as they were told. Then she told them to walk as a group toward the corner that was rising. From the kitchen to the front of the house they walked as a unit, as the wind screamed and rain pounded deafeningly on the roof. Then they walked back in the other direction as another corner of the house began to lift.

And so it went, back and forth for the duration of the storm, 15 children and one woman walking with the wind, holding the trembling house down with the weight of their bodies.

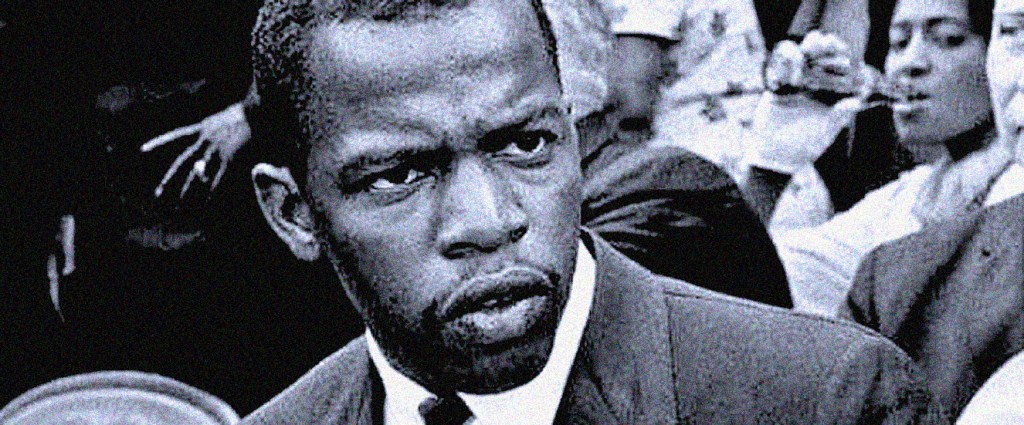

That memory stayed with John Robert all his life, as he grew up to be a fighter for justice for his people, civil rights activist and eventually US Congressman John R. Lewis. At lunch counter sit-ins, and on the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and on the Freedom Rides, on the march from Selma to Montgomery, and through so many other fights for justice, he was struck more and more by how our country is a little like that house, rocked time and again by storms that threaten to blow it apart. But every time, there are people of goodwill who join hands and walk toward the corner of the house that’s in trouble. Then another corner wobbles, and they go there.

(John Lewis on the dais at the March on Washington, 1963)

For John Lewis, this was the essence of a good life, to respond with decency, dignity, and sister and brotherhood to the challenges that face us. Together. When necessary, going toward trouble, walking with the wind.

So, that’s what I’ve got for you:

A big part of making your way in the world comes from knowing when to act as an individual, and when to join hands with other people.

Remember to speak up, even if it might cost you. And think for yourself; it’s fun, it makes the world more interesting, and it makes you more interesting.

And it just might be our best chance against those zombie goats.

*********************

(The John Lewis story is drawn from the prologue of his book Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement <Harvest Books, 1999>, which he co-wrote with Michael D’Orso. It’s an astoundingly good read, moving and inspiring, and it takes you in deep.)

Leave a comment